|

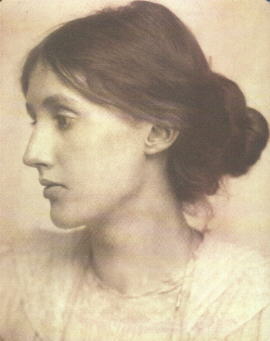

VIRGINIA

WOOLF: WRITING THE SUICIDE

|

|

by

Malcolm Ingram |

|

Malcolm

Ingram , MD, is Retired Consultant Psychiatrist, at the Southern

General Hospital , Glasgow, Scotland. He is Former Lecturer in

Psychological Medicine at University of Glasgow. His research

interests and publications include work on obsessional neurosis and

personality, psychiatric aspects of abortion, and the efficacy of

teaching. He has always had an interest in psychiatry and literature,

lecturing on Johnson and Boswell and James Joyce, and also on

psychiatric disorder in composers such as Schumann and Donizetti. He

also studies the diary or journal as a literary form.

|

On the 28th March, 1941, aged fifty-nine, she drowned herself in

the river Ouse, near her Sussex home. Two suicide notes were found

in the house, similar in content; one may have been written ten days

earlier, and it is possible that she may have made an unsuccessful

attempt then, for she returned from a walk soaking wet, saying that

she had fallen. They were addressed to her sister Vanessa and to her

husband Leonard. To him, she wrote:

'Dearest, I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can't go

through another of those terrible times. And I shan't recover this

time. I begin to hear voices, and I can't concentrate. So I am doing

what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest

possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could

be. I don't think two people could have been happier till this

terrible disease came. I can't fight any longer. I know that I am

spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I

know. You see I can't even write this properly. I can't read. What I

want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have

been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say

that - everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would

have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your

goodness. I can't go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don't think two people could have been happier than we have

been.

V.'

After writing this note she left Monk's House, Rodmell - her home

- at 11.30 am, taking her walking stick, and crossed the water

meadows to the river, where she put a large stone in the pocket of

her coat.

Her body was not recovered until the 18th April when it was

discovered by children a short way downstream. Her husband

identified the body, and an inquest was held the following day at

Newhaven. The verdict, in the standard phrase of the time, was

'suicide while the balance of her mind was disturbed.' She was

cremated privately at Brighton on 21st April, and her ashes

scattered under one of the pair of elms at Monk's House.

What symptoms and events preceded her death? For how long had she

been depressed? Some forty years later, her husband, Leonard Woolf,

described her last year and suicide in one of the volumes of his

autobiography. Feminist critics have been suspicious of his motives,

but he was a pedantically accurate man who kept brief but detailed

daily records of his activities throughout the marriage. His account

is, at the very least, chronologically accurate, as he had access to

these diaries, and to his wifes'lengthier journals, both made at the

time of the events. He describes - the accurate timing is typical -

'319 days of headlong and yet slow-moving catastrophe' between

sending off the proofs of her biography of Roger Fry to the printers

on 13th May, 1940, and her suicide on 28th March, 1941. Yet he

writes that she was only ill latterly - 'loss of control of her mind

began only a month or two before her suicide.' While conceding that

the period between April 1940 and January 1941 was stressful for

everyone, especially in Southern England, with air-raids and the

mounting threat of invasion, Leonard thought 'she was happier for

the most part, and her mind more tranquil than usual.'

In May and June, 1940, they had discussed between themselves and

with friends what action they would take in the event of a German

invasion. They had no illusions about the way in which a politically

active, intellectual Jew and his wife would be treated by the Nazis.

'We agreed that if the time came we would shut the garage door and

commit suicide,' Leonard wrote. In June, 1940, Adrian Stephen, her

psychoanalyst brother, provided the Woolfs with lethal doses of

morphine to use in the event of a German invasion. This was a joint

decision by the couple, and not an indication of depression or

morbid suicidal thoughts on her part. Nor did she use the morphine

when she decided to end her life.

In February 1940 Virginia contracted 'influenza', and spent the

first three weeks of March in bed. Such attacks were not uncommon

over the last twenty years of her life. It is difficult to know if

they were common colds, aggravated by bronchitis, and whether they

elicited minor mood swings, which were then cautiously managed by

her husband and her doctors. As in this case, the time spent in bed

was often disproportionate to the diagnosis of 'influenza'. At other

times these symptoms coexisted with lengthy headaches which

incapacitated her, and which, unless treated with bed rest, could

lead to overt mood swings.

For the rest of the year she was energetic and productive; in

November, 1940, she was writing three works simultaneously. By

December she had finished the draft of her last novel, Between the

Acts. Her letters in that month often mention shaking hands, and by

the end of the year there is a hint of depression and self-criticism

when she writes to her friend and general practitioner Octavia

Wilberforce: 'I've lost all power over words, can't do a thing with

them.' The effects of war were being brought home to them; their

London house and business in Mecklenburg Square had been bombed, and

all its furniture, their papers, and their printing press arrived at

the cottage, and had to be sorted and accommodated. But by early

1941 she was planning to re-read the whole of English literature and

embarked on the project. In February Elizabeth Bowen visited her

fellow writer, found no sign of illness and years afterwards chiefly

recalled her loud laughter.

Leonard Woolf had noted the first symptoms of 'serious mental

disturbance' on 25th January,1940, her birthday, while she was

revising the draft of Between the Acts. She had enjoyed writing the

book, finishing the first draft at the end of the previous November,

and writing then: 'I am a little triumphant about the book...I've

enjoyed writing almost every page.' When her final depression became

entrenched, the idea that the book was a failure became a firm

conviction, but during this revision the fear arose, only to pass

off after ten or twelve days.

Leonard always took immediate action. 'For years I had been

accustomed to watch for signs of danger in V's mind; and the warning

symptoms had come on slowly and unmistakeably; the headache, the

sleeplessness, the inability to concentrate. We had learnt that a

breakdown could always be avoided, if she immediately retired into a

cocoon of quiescence when the symptoms showed themselves. But this

time there were no warning symptoms.' The only other breakdown to

have a sudden onset had been in 1915 - her most severe and lengthy

illness.

The writer John Lehmann, at that time working for the Woolfs at

the Hogarth Press, saw her in the weeks before her death, and

received one of Virginia's last letters. He had been asked to read

the final draft of Between the Acts, and by this time she was

convinced that the book was worthless. In his Recollections Lehmann

describes her state of mind in March, 1941. 'I became more and more

conscious of the fact that Virginia seemed unusually tense and

nervous, her hand shaking now and then, though she talked absolutely

clearly and collectedly.' She had brought the draft of Between the

Acts, and 'Virginia immediately began, now rather confusedly, to say

that it was no good at all, couldn't be published, must be scrapped.

Very gently, but with great determination, Leonard rebuked and

contradicted her...'

In the next few days Lehmann read the draft of the novel: 'The

first thing tht I noticed was that the typing - her own typing - and

the spelling were more eccentric, more irregular than in any

typescript of hers I had seen before. Each page was splashed with

corrections, in a way that suggested that the hand that had made

them had been governed by a high voltage electric current.'

Lehmann then received a letter from her saying the book was silly

and trivial, and couldn't be published, with a covering letter from

Leonard saying that she was on the verge of a breakdown. Both were

probably written the day before her death. 'By the time they reached

me it was all over.....I was aware ...of an undertow of sadness,

melancholy, of great fear, but the main impression was of a creature

of laughter and movement.'

Another witness was her general practitioner, Octavia Wilberforce,

a descendant of William Wilberforce. At that time she was also

running a dairy farm near at hand, and for some months had kept the

Woolfs supplied with extra butter and cream in that time of

shortages. She had visited Monks House frequently from January 1941

on, but a formal consultation did not take place until 17th March.

Three days earlier Virginia had discussed one of her last short

stories with Dr Wilberforce and told her that it had left her 'desperate

- depressed to the lowest depths.'

Dr Wilberforce when newly qualified worked as a locum physician

in Graylingwell Asylum for a month or two, but her psychiatric

knowledge, like that of most doctors at the time, was rudimentary,

although she had read some Freud. At Leonard's request she examined

Virginia on the 26th March, the day before her death. The doctor was

ill with influenza and rose from her sick-bed for the consultation.

Virginia told her that it was 'quite unnecessary to have come' and

did not answer her questions frankly. She was generally 'resistive',

and demanded a promise that she would not be ordered to have a 'rest

cure' - that is, an admission to a psychiatric nursing home - before

she would submit to a physical examination.

Octavia Wilberforce, in letters written over the next few days is

obviously taken aback by the suicide. She phoned a physician friend

for reassurance. On the 28th she wrote: 'I am haunted by V and my

own failure ot help'. She visited Leonard who told her that when he

married he knew nothing of her 'affliction'. He told her of its

recurring nature, the many opinions they had had, and of her happy

nature. On the 29th she visited him again, when he told her that

after their visit on the 26th Virginia seemed cheerful and quite

different.

But she had been depressed earlier. and not only for the ten or

twelve days noted by her husband. Her diary for the 8th March reads:

'I mark Henry James's sentence: Observe perpetually. Observe the

oncome of age. Observe greed. Observe my own despondency. By that

means it becomes serviceable.'

Whatever the duration, Leonard was seriously concerned about her

by the 17th of March. She was able to dissemble. Even after that

date she wrote coherent and cheerful letters to a number of friends.

She probably tried to conceal her depression and her suicidal ideas

from her doctor and her husband. Dr Wilberforce saw her earlier on

the 22nd March. Virginia had wanted to interview her about one of

her relatives - a cousin Octavia - planning to write a portrait of

her. At that time Virginia was proccupied with her own forebears,

especially her father. Dr. Octavia tried to jolt her by telling her

she was her own worst enemy. She wrote later: 'I thought this family

business was all nonsense, blood thicker than water balderdash.

Surprised her anyway.' It is clear that the doctor had no inkling of

the imminent suicide. At this point Leonard cannot have informed her

in detail about his wife's previous history, especially her past

suicidal attempts, or their serious nature.

Some critics have made much of the war and the threat of invasion

as 'causes' of her suicide. Immediately after her death Leonard and

Octavia Wilberforce felt that the war had reminded her of her

illness in the first world war. Current events turned her mind to

death, but not to suicide, until near the end. Only six months

before her death, on 2nd October 1940, she made an entry in her

journal, during a time of air-raids, imagining what it would be like

to die in one. 'I shall think - oh I wanted another ten years - not

this.....'

She recorded her views on suicide, while in good health, in the

thirties, in correspondence with the composer Ethel Smyth, one of

the few friends in whom she confided about her past illnesses. On 30

10 30 she wrote: 'By the way, what are the arguments against

suicide? You know what a flibberti-gibbet I am: well there suddenly

comes in a thunder clap a sense of the complete uselessness of my

life. It's like suddenly running one's head against a wall at the

end of a blind alley. Now what are the arguments against that sense

- "Oh it would be better to end it"? I need not say that I

have no sort of intention of taking any steps: I simply want to know.....what

are the arguments against it?'

Six months later, on 29 3 31, she returns to the subject: 'Why

did I feel violent after the party? It would be amusing to see how

far you can make out, with your insight, the various states of mind

which led me, on coming home, to say to L:- "If you weren't

here, I should kill myself - so much do I suffer."'

A few days later she heard Beatrice Webb discussing suicide, and

on 8th April wrote to her: 'I wanted to tell you but was too shy,

how much I was pleased by your views upon the possible justification

of suicide. Having made the attempt myself, from the best of motives

as I thought - not to be a burden on my husband - the conventional

accusation of cowardice and sin has always rather rankled.

Suicide was an ever-interesting topic, and she could regard it

with cool detachment when she was well, although she allows herself

here to believe that her past attempt was reasonable and altruistic..

As for death, her adolescence was so replete with deaths of parents

and siblings that for the rest of her life she felt the presence of

the dead, and their memory, as strongly as that of the living, to

the extent that her sense of reality was sometimes disturbed by the

vividness of the past.

From these accounts an accurate diagnosis of her final illness

can be made. From the suicide note alone, most psychiatrists would

make a confident diagnosis of severe depression. She says that she

is not only depressed, but going 'mad' again; she is beginning to

hear voices. She can't concentrate, can't read or write. She shows

self-blame, believing that she is spoiling her husband's life. She

feels hopeless, can't go on any longer. She believes suicide is the

best course. Lehmann's memoir shows that her self-criticism was

quite unjustified, exemplified by her low opinion of her novel which

she had thought well off a few months earlier. Reassurances about

the book and about her recovery had been frequent and unavailing.

When examined by Dr Wilberforce the day before her death, she had at

first refused to discuss her symptoms or to admit that there was

anything wrong. Each of these symptoms is typical of severe

depression. The only atypical item in the letter is her clear

admission that she is ill - that she is going mad and has a 'terrible

disease'.

With this well-documented, and ultimately fatal episode in mind,

it will be easier to trace the long and complicated history of her

past attacks, both serious and mild.

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andreasen, Nancy C. Creativity and Mental Illness. Prevalence

rates in writers and their first degree relatives. Am J Psychiat,

1987, 144:10, 1288-1292

Annan, Noel Gilroy Leslie Stephen, The Godless Victorian London,

MacGibbon and Kee, 1951 and 1984

Anon Who Was Who, 1916-1928. Sir George Savage

Blodgett, Harriet Centuries of Female Days, Rutgers Univ Press, 1988

Caramagno, Thomas. Manic-depressive Psychosis and Critical

Approaches to VW's Life and Work: PMLA. 1988, 103,1. 10-23

Caramagno, Thomas C: The Flight of the Mind: Virginia Woolf's Art

and Manic-Depressive Psychosis. Berkeley, University of California

Press, 1992

Chase, Kathleen : Legend and Legacy: some Bloomsbury Diaries: World

Literature Today, 1967,61:2, 230-233, Oklahoma

Craig, Maurice: Psychological Medicine. 3rd Edn. London, J and A

Churchill.

DeSalvo, Louise: The Impact of Childhood Sexual Abuse on her Life

and Work. The Womans Press, 1989.

Dinnage, Rosemary : Times Literary Supplement,1980, 18th April

Dobbs, Brian: Dear Diary...: Some Studies in Self-interest London,

Hamish Hamilton, 1974

Dunn Jane A Very Close Conspiracy - Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf

: Jonathan Cape, London 1990

Feinstein Sherman C Why they were afraid of VW: perspectives on

juvenile manic-depressive illness ; Annals Am. Soc. for

Adolesc.Psychiatry, 8 , Chicago UP, 1980

Gindin J Virginia Woolf and Biography , Biography 4, Spring 1981

Goldstein, Jan Ellen The Woolf's response to Freud: water-spiders,

singing canries, and the second apple : Psychoanalytic Quarterly,1974,43,438-476

Goodwin FK and Jamison KR Manic-Depressive Illness: NY, Oxford

University Press, 1990

Griffin, G Virginia Woolf and autobiography : Biography 4, Spring

1981

Hare, EH Existential Theory of Psychiatry : BMJ, 1982,284, 1313-4

Hill, Katherine C. Virginia Woolf and Leslie Stephen: History and

Literary Revolution: PMLA, 1982,97,351-362

Hussey, Mark: Virginia Woolf - A to Z. Oxford University Press,

1996

Hyman, Virginia Concealment and Disclosure in Sir Leslie Stephen's

Mausoleum Book: Biography III, p127

Jalland, Pat: Octavia Wilberforce. The autobiography of a pioneer

woman doctor. Cassell, 1989

Jamison, Kay R.: Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in

British writers and artists. Psychiatry,1989, 52, 125-134.

Jamison, Kay R.: Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and

the Artistic Temperament. Free Press, 1993

Kamiya Miyeko Virginia Woolf:An outline of a study on her

personality, illness, work : Confinia Psychiatrica(Basel) 1965 8

189-204

Kennedy Richard: A Boy at the Hogarth Press: Penguin 1978

Kenney, Susan M : Virginia Woolf and the Art of Madness

Massachusetts Review: 1982,23,161-185

King, James; Virginia Woolf. Hamish Hamilton, London,1994

Lee, Hermione: Virginia Woolf. Chatto and Windus, London.1996

Love, Jean O.: Virginia Woolf: Sources of Madness and Art: Berkeley,

Univ of California Press, 1977

Ludwig, Arnold M.: The Price of Greatness: Resolving the

Creativity and Madness Controversy. Guilford Press, 1995

Marcus, Jane: Virginia Woolf and Bloomsbury; a centenary

celebration: Basingstoke, Macmillan, 1987

Marler, Regina: Bloomsbury Pie. 1997

McLaurin, Allen : Virginia Woolf: The Echoes Enslaved : Cambridge UP

1973

Meisel,P and Kendrick, W (Eds) : Bloomsbury/Freud; the letters of

James and Alix Strachey 1924-1925: Chatto and Windus, London, 1986

Mepham J: Trained to silence: London Review of Books, 1980,

20/11-4/12

Morizot, Carol Ann: Just this side of madness: creativity and the

drive to create: Houston: Harold, 1978

Morrell, Otteline ed Gathorne-Hardy, R.: Ottoline at Garsington:

Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915-1918

Nicolson Nigel(Ed) Letters of Virginia Woolf Vol 2

Nicolson, Nigel Portrait of a Marriage Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973

Noble, Joan R.(Ed.): Recollections of Virginia Woolf. London.

Peter Owen. 1972

Oppenheim, Janet "Shattered Nerves": Doctors, Patients,

and Depression in Victorian England : New York, Oxford, Oxford

University Press, 1991

Paykel E S: Life Events and Early environment; in Handbook of

Affective Disorders, 1982

Plomer William: Autobiography , Cape 1975

Poole, Roger: The Unknown Virginia Woolf: London, Humanities Press.

3rd Edn,1990

Richards R et al : Creativity in Manic-depressives, cyclothymes,

their normal relatives and control subjects: J. Abn. Psychol.

1988,97, 281-288

Rose, Phyllis: Woman of Letters: A Life of Virginia Woolf. NY:Oxford;

Routledge, 1978

Rosenbaum S.P.(Ed): The Bloomsbury Group: A Collection of Memoirs,

Commentary adn Criticism. Croom Helm; University of Toronto, 1975

Savage, George H.: Insanity and Allied Neuroses. Cassell, London,

1884

Showalter, Elaine : The Female Malady:Women, Madness, and English

Culture,1830-1980: New York, Pantheon, 1985

Silver, Brenda R : Virginia Woolf's Reading Notebooks : Princeton

Univ Press, 1983

Slater, Eliot and Meyer, A. : Contributions to a pathography of

the musicians: Robert Schumann, Confinia Psychiatrica,1959, 2,

65-94.

Spalding, Frances: Vanessa Bell. Weidenfeld and Nocholson, London,

1983.

Spotts (Ed) : The Letters of Leonard Woolf: Bloomsbury, 1990

Stape,J.H.:Virginia Woolf - Interviews and Recollections. Macmillan,

1995

Trombley, Stephen: All that summer she was mad: Virginia Woolf

and her doctors: London, Junction Books, 1981

Wolpert E S Manic-depressive Illness: History of a Syndrome : NY

International University Press, 1977

Woolf, Leonard: An Autobiography,

Vol.1,1880-1911;Vol.2,1911-1969.Oxford, Oxford University Press,

1980

Woolf, Leonard: Letters,ed. Spotts,F. New York:Harcourt, Brace,

Jovanovich,1989

Woolf, Virginia: A Passionate Apprentice; The Early Journals,1897-1909.

Ed. Leaska, M.A. Hogarth Press, London. 1990

Woolf Virginia: Diary. Ed. Anne Olivier Bell. 5 vols. London,

Hogarth Press,1977-84

Woolf Virginia: On being ill: in Essays Vol 4.

Woolf, Virginia: Collected Essays, 4 Vols. London, Hogarth Press,

1966-7

Woolf, Virginia: Congenial Spirits: The Selected Letters of

Virginia Woolf, Ed. Joanne T Banks. London, The Hogarth Press,1989

Woolf, Virginia, ed Leaska, M A : A Passionate Apprentice: the early

journals, 1897-1909: London, Hogarth Press, 1990

Zwerdling, Alex: Virginia Woolf and the real world : Berkeley London

California Univ Press, 1986

|

|