Insights to Art

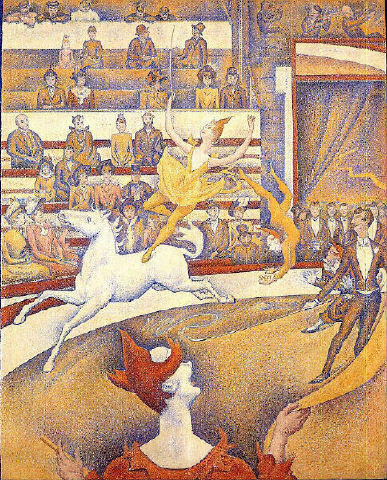

Seurat's The Circus

Seurat, The Circus - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Georges Seurat, The Circus (1890-91; 185cm x 152cm)

After Impressionism

Georges Seurat (b. 1859, d. 1891) is one of those painters - along with Gaugin, Van Gogh and others - who are labelled Post-Impressionists. After Impressionism had broken away from a good number of the traditional canons of painting, many of the Post-Impressionists felt that they needed to create some order out of the attractive but rather trivial chaos of their forerunners. A logical and precise person by nature, Seurat was very interested in the theoretical side of art. He studied colour theories as well as academic treatises on vision, putting his fascination with light and shade, colour balance and tone into practice from his early sketches and paintings onwards. His studies in this field led him to develop his typical style of applying colour, known as "Pointillism". Nonetheless, he was also very much interested in form, shape and proportion, as can be seen in his The Circus (Le Cirque, in French) which was exhibited in 1891, albeit not quite finished, shortly before his death. As with Gaugin and Van Gogh, however, the first great innovative influence on Seurat's work came from the Impressionist painters. His use of juxtapositions of colour ultimately stems from the work of Monet, Renoir and Pissarro; his use of space on the canvas - shunning artistic effects that give a sense of space, allowing figures and objects to be cut by the frame - also reflects the work of painters such as Monet, Cézanne and Degas.

Colour and Pointillism

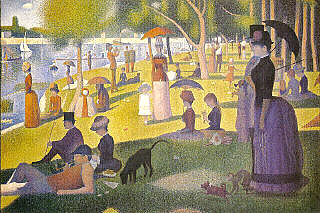

While Monet, Renoir and other Impressionist painters added dashes of colour to their canvases until the final effect was achieved, Seurat's systematic examination of colour led him to juxtapose colours with almost scientific accuracy. He developed a technique that uses small dabs or dots of divided, separate primary colour that are so close to each other as to almost merge visually. Seurat preferred to call this technique "Divisionism", but it is more commonly known by the term "Pointillism". His Bather at Asnières (Une Baignade à Asnières, 1883-84) and more especially his "Sunday Afternoon on the Grande Jatte" (Un Dimanche à la Grande Jatte, 1884-85) are his true Pointillist masterpieces. And although in his later works Seurat's interests were more concerned with form and shape, he remained true to his Pointillist technique, as is clear in The Circus. Seurat's interest in contrasts of colour also went further in his later works, however, and the warm, "uplifting" orange colours that dominate The Circus are balanced by the white areas and offset by the blue frame which points to the dullness of the outside world.

Georges Seurat, Sunday Afternoon on the Grande Jatte (1883-84)

Lines and Curves

In his Sunday Afternoon on the Grande Jatte, Seurat uses an interplay of straight lines (tree trunks, hats, etc.) and curves (sunshades, feminine forms, etc.) as well as angles of vision, skilfully playing with shapes and space in a deceptively simple, almost one-dimensional work. Seurat's growing interest in shape and form led him to attend a series of lectures given at the Sorbonne in the mid-1880s by the mathematician Charles Henry, who was to become his close associate for the latter few years of his short life. Henry's theories on mathematical curves and their symbolic and emotional associations were clearly a great influence on Seurat's last few paintings, such as The Models (Les Poseuses, 1888) and Le Chahut (1889-90), but nowhere more so than his The Circus, which he painted between 1890 and 1891. Seurat described art as a "harmony of contrasts". And his "Divisionsist" contrasts of colour were, in his later paintings, also accompanied by contrasts of straight lines and curves. In The Circus, there is an extreme use of curved lines for the bright, dazzling foreground circus performers and the horse; the background, on the other hand, is linear and inert. According to the theories employed by Seurat in this work, horizontal lines are restful, while curving upward lines give happiness and movement. As in the Grande Jatte, there is a variety of angles of vision (of perspectives), and there is an overall dynamic play of lines, curves and the patterns they create.

Toulouse-Lautrec, the Circus and Things to Come

Seurat's last paintings of Le Chahut and The Circus also owe a good deal to the posters of the time, especially those of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules Cheret. Like Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat was fascinated by the circus, and both artists filled notebooks with sketches of circus scenes and artists. The night clubs of Pigalle and popular entertainments such as circuses were hardly the stuff of art up until Toulouse-Lautrec's bold moves away from the bourgeois art circles. And just like Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat was interested in social class, from upper to lower. The spectators in the background of his The Circus are a fascinating study of animated upper-class characters in the front seats and wearied lower-class figures further back. The almost cartoon-like quality of Seurat's ringmaster or foreground jester, as well as the strong use of colour for the figures are in part an influence of the paintings and posters of Toulouse-Lautrec. The last decade of the 19th century was also the breezy, care-free period leading up to the Belle Époque and the start of the light-hearted Art Nouveau style of art and architecture, and the curls and swirls of The Circus are in many ways a step in the direction of upcoming styles and fashions.

© Nigel J. Ross, 2003

Home |

Publications |

Dictionaries |

English Lang. |

Art Insights |

Travel |

Links | ||||||