|

|

![]() Patron Saint

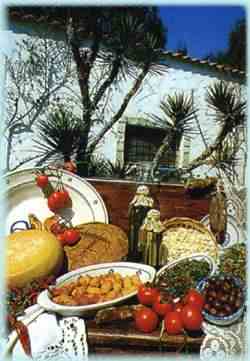

Holidays and Gastronomy

Patron Saint

Holidays and Gastronomy

The people of Lecce pour the best of their technical and artistic skills into the preparations for the saints' feast days. On these spectacular occasions the towns and villages come to life with decorations, coloured paper balls, lights, fireworks and musical bands, which in turn are exported all over the world. Some of the more important festivals include Sant'Oronzo in Lecce (August 26); Sant'Anna at Vernole (iuly 26); the feast of the Assumption at Martano (August 14); the processions to the sea in Otranto (August 14) and in San Foca (August 21)-occasions on which the true character of Salento comes to the surface. These festivals are characterised by the special Salento flair for aesthetics, theatricality and the spectacular, the ancient essence of this peninsula's culture that, despite all the intervening social changes, has been preserved with the traditions over the centuries. The atmosphere of the popular festival brings out the authentic Salentine spirit, a blend of wisdom, wit, cordiality and irony.

| Times like these are also the best occasions for sampling the products of a unique cuisine: sweets, with strong Oriental flavours, such as fruttoni, mostaccioli or copeta (almond and honey nougat); meat dishes such as roasted lamb entrails, turcinelli delicacies of horsemeat with sauce, moniceddhi, that is snails collected during the underground hibernation period, thus still covered in a whitish secretion (mpannate). These and many more dishes are served in the "putèe", the typical Salento restaurants where the traditions of popular cuisine are preserved. The San Giuseppe tables form part of another culinary tradition that is still alive in villages such as Surano and Giurdignano. This devotional practice which has been handed down within families entails days of preparation for a speciai menu. The dishes are surprising: home-made spaghetti, cakes with honey and accompanied with fried fish, a complex, dried salted cod sauce, round bread rolls with mysterious insignia, pod-shaped honey cakes that allude to ancient Egyptian divinities. |

All of these dishes have borrowed directly from cultures of the Mediterranean Basin and beyond, attesting to Salento's role as the meeting point of the most ancient of civilisations. |

![]() Legends

and Rituals

Legends

and Rituals

The fascino (the word means charm) and the laùru are two examples of the popular credences involving traditions, superstitions, or ritual practices, most of which are connected to specific days. The fascino is the belief in certain individuais' powers, often unknown to them, to provoke harm, illnesses and deaths by way of a simple glance or by invocations cloaked in well-wishing words. Children are often favourite fascino victims and this explains why one should never say to a chiid: "What a lovely child! , without adding immediateiy Bless the child! , maybe even with a hint of irony. The Iaùru concerns a type of imp and its name derives from the laurel groves (laureti) where the littie spirit used to live. The laùru was given to visiting and even moving into other people's homes, where by night it dedicated itself to disturbance and vexation. Laùrus liked to clatter pots and saucepan lids, to plait horses' manes, or to sit on the stomachs of sleeping people. One story tells of a tormented soul who was driven to move house in an effort to free himself from the laùru. He loaded his cart with all his household belongings and set off. When he came to a fork in the road a passing acquaintance asked him,'Where are you going, friend? The answer came from a little voice at the bottom of a saucepan that said, "We are moving house!" Religious and mithological rituals that are common to all the Mediterranean cultures, from the_Greek to the Arab civilisations continue to survive in the festivals Superstitions and Bonfires.

In Salento it s customary to light bonfires for speciai occasions.. Such fires are intended both to propitiate and to purify, the purpose being to ensure a good harvest, yet they also recall the burning of witches at the stake, thus the cleansing of the iIls and afflictions that the ancient rural world ascribed to these witches. On January 17 in Novoli the "focara (fire) burns 40,000 bundles of vine branches and reaches a height of 40 metres. The fire is a spectacular sight and the celebrations are accompanied by offerings of local dishes, arts and crafts, concerts and, rnost irnportantly, firework displays.

dal film "Sangue vivo" di E. Winspeare |

|

![]() Music and Dance in

Salentine Tradition

Music and Dance in

Salentine Tradition

|

The use of music and dance for both ceremonial and therapeutic purposes is one of the distinctive features of this ancient culture, and probably dates back to before the arrival of Greek influence. These arts are imbued with rich iconographies that hark back to distant archetypal myths common among many other Mediterranean civilisations. Dionysism is the underlying force in tarantism, which is probably the most mysterious and intriguing phenomenon of Salento folk culture. This ancient exorcist practice dating back to the Middie Ages has not yet completely died out. Men and women who believe they have been bitten by the tarantula go on a pilgrimage to Galatina on the San Paolo's feast days (June 28 and 29). The tarantula's bite induces a mortal languor and the pilgrimage liberates the victim from these effects, as does the use of colours, music and dance. Thus the role of the small orchestra-the main instruments are the traditional guitar, violin, mandolin and tambourine is all important. The band goes to the victim's house and incites the bitten one to dance, sometimes for days on end. Recourse to St. PauI is explained by Christianity's effort to provide a substitute for the ancient pagan cult of serpents. The tarantula might also represent a totemic animal whose origins are lost in the mists of time, prior to the cult of Menadaism, Corybantism, or the Dionysiac festivals which tarantanism evokes with its hedonist and frenzied traits. The superb rhythmic music leads the victims towards their liberation, with sounds that range from the gloomy to the poignant, culminating in an extraordinary crescendo.

|

This music is now played by various revival groups and offers an interesting example of the survival of Salento folk music.

|

|

|

|

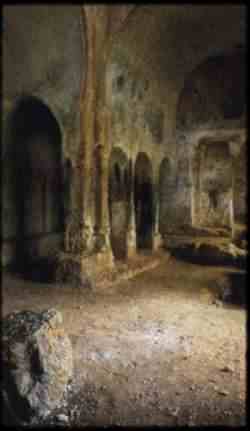

![]() Crypts

and churches

Crypts

and churches

As to the hermit-byzantine crypts, they are linked to the iconoclastic fight sparked off by Leone III, the emperor of Byzantium, in the 8th century, when a multitude of hermits stramed to Salento. Leading an ascetic life, the hermits first occupied the caves along the coast and then the ones spread in the hinterland, converting them into small churches and lodgings for the night. In those places a miracle happened: the apses and walls were covered with marvellous frescoes showing saints from eastern countries and scenes from the gospel. Many of them preserve their whole beauty still today. In addition to the crypts, the churches, jewels of art and faith, increase Salento's broad heritage. Some of them date back to the lower middle ages under the Byzantines first (S. Peter's in Otranto) and the Normans then in Veglie and all the others that you fìnd in the Salento (S. Nicola di Casole), to discover all the passion and enthusiasm which the anonymous frescoes put in giving life to their colours.

|

|

The baroque deserves more atttention since it represents the most dramatic point of contact between faith and art; it reaches its highest Ievel in the architectural eccentricity of its renowned world capital: Lecce. Santa Croce Basilica alone is worthy of a trip to Salento from the farthest places in the world. Lecce is the triumph of baroque and of Lecce stone, starting from the magnificent facades of its churches, monasteries, public buildings and private houses till the humblest of its balconies and portals.

|

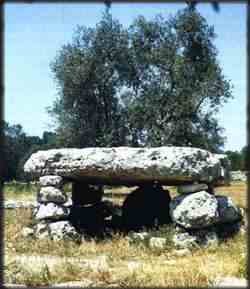

The megaliths are spread all over the province and can probably be dated back to the Bronze Age, they are therefore chronologically later than the analogous and impressive megalith phenomenon which developed along the Atlantic coasts of Europe. Menhir, dolmen and specchie (mounds) represent one of the most spectacular and also most mysterious moments of old Salentine history placed as they are between legend and supposition, in the mortifying absence of certainty. |

Menhirs are stones, roughly squared and placed vertically in the ground, of various dimensions and rectangular section, they are located mostly in isolated places and positioned with the wide prism tace towards the sun. This last detail suggests that various ritual elements were interwoven, for example the phallic cult and worshipping the sun with a more practical and necessary function, linked to the changing of the seasons, e.g. use as an astronomical observatory or as a meeting place at certain times of year to take important decisions. There were those who believed in the mythical idea that they served as severe guardians of precious coins and fabulous treasure.

Dolmens, on the other hand, are constructions made up of horizontal covering slabs with a series of stone blocks supporting them forming a large burial room, giving credence to the hypothesis that they were funeral monuments or in any case destined in some way to celebrate the Journey to the hereafter. A common element of nearly all the Salentine dolmens is their entrance, which faces east.

As the first civilised and organised inhabitants of the area now occupied by the provinces of Lecce, Brindisi and Taranto, the Messapians created a civilisation that was very advanced for its time, evidence of which, sometimes very impressive evidence, has come to light in recent years, during the numerous excavations that have taken and are taking place all over the area.

| Archaeological and epigraphical heritage of great interest can be admired at Lecce's Provincial Museum (the oldest in the region), Gallipoiii's Civic Museum, Alezio's Archaeological Park, Ugento's Civic Museum, and for an overall picture in Tarantos National Museum, tull of statues, Messapian vases, fibulas, craters, painted and glazed pottery, lamps, imported and local terracotta. |

|

| SCUOLA PORTA D'ORIENTE via Madonna del Passo 73028 Otranto (LECCE) e-mail: porta.doriente@libero.it web site: www.porta-doriente.com tel 0039 338 4562722 tel/fax 0039 0836 801964 |