Aqueducts

(Acquedotti). Ancient Rome had 7 hills, but 11 aqueducts. Rome's greatness expanded as the volume of water brought into the city grew, and when the Barbarians cut the aqueducts, Rome fell.

(Acquedotti). Ancient Rome had 7 hills, but 11 aqueducts. Rome's greatness expanded as the volume of water brought into the city grew, and when the Barbarians cut the aqueducts, Rome fell.

There are still places in the city where you can see spans of these antique engineering masterpieces, notably in Via di San Gregorio, and at Porta Maggiore. Rome's grandeur is also demonstrated by monumental remains of aqueducts on the vast plains Southeast of Rome at Parco Appio Claudio - and of course in France, Spain and Great Britain.

Aqueducts were channels, lined with waterproof cement and covered with stone lids, leading the water collected from mountain springs or lakes down a shallow grade (1 in 1,000) to the big city. At the water's source Romans constructed large reservoirs not only to assure a continual flow but also to increase the pressure of the water at the start of its multi-mile trip to Rome.

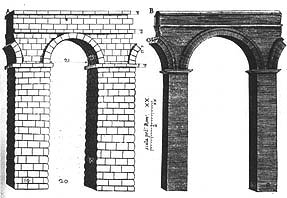

The watercourse often started through an underground channel, but to cross ravines, rivers and valleys the aqueduct was lifted on lengthy aerial bridges, sometimes two or three tiers high, of stone, brick or concrete.

The watercourse often started through an underground channel, but to cross ravines, rivers and valleys the aqueduct was lifted on lengthy aerial bridges, sometimes two or three tiers high, of stone, brick or concrete.

On arrival in downtown Rome, the water was fed through pipes of lead, sometimes terracotta or wood, to public fountains and public buildings, notably baths. An appreciable part of Rome's budget was spent on the never-ending repairs needed to keep fresh, clean water streaming into the city.

At its height, ancient Rome was a city flowing with water, which effectively slaked the citizen's thirst, cleansed their bodies and carried away their sewage. During the Barbarians' various sieges, more and more of this water was chopped off, until Civilization, as the Romans knew it, literally dried up.

That is one aqua-theory of history; another is that daily consumption of water from lead pipes, as well as eating from lead-based vessels, over the years gave the Roman race lead-poisoning until it could no longer stand up to its enemies.

The third, and more authoritative, theory is that the Romans' pampered way-of-life, exemplified by the over abundance of domestic water and baths, made them so soft and over confident that the Goths and Visigoths could just blow them away.

For almost a millennium Romans were again reduced to using the polluted Tiber. Health and cleanliness suffered. The Dark Millennium was also the dirty millennium.

Finally, the Renaissance Popes started rebuilding the aqueducts and Romans started washing and having sanitation again. Today, three of the ancient watercourses are supplying part of the fresh clear water that again runs plentifully through the city, thanks also to some modern aqueducts.

But the waters are never mixed, so that you will still see Romans drawing water from one of the thousands of street fountains - indicating that either their taps have run dry at home or that they prefer this particular Aqua, perhaps for what they consider its spiritual attributes.

| Aqueducts History 8C-4C BC. The early Romans, finding the Tiber River polluted, drew their water from various springs and wells dotted around the city. 312 BC. The Senate decided that overpopulation had exhausted the local supply and entrusted the job of bringing in water from the outside to Appius Claudius Caecus, builder of the Appian Way. This first aqueduct, Aqua Appia, was almost entirely underground. 144 BC. Aqua Marcia, the first and longest elevated aqueduct, lead to the Capitoline Hill. 33 BC. Marcus Agrippa in a year repaired all 4 existing aqueducts and built another, Aqua Julia, as well as 500 fountains and 700 public basins and pools. 20 years later he built the first grand imperial Bath for which he constructed another water course, Aqua Virgo. (see: Trevi Fountain). 410 AD. When the Goths first sacked Rome, the 11 aqueducts were supplying 1212 public fountains and 937 public baths, including the 11 grand imperial thermae. Roman society was spoiled rotten and very vulnerable. 537. Aqueducts cut by Vitges the Goth. Belisarius had them filled in to prevent Goths creeping through the giant ducts. 1453. Finally, after 900 years, Pope Nicholas V had the great Florentine architect Alberti restore Aqua Virgo, calling it Aqua Virgine. |