Close examination reveals that there is no great tradition of the nude, at least when compared to other genres such as landscapes and portraits, in what can now be considered the long history of photography. The reason is not to be found in the fact that from the very beginnings of the new technology photos of nudes (for the most part female nudes to fire prurient male fantasies through the clandestine diffusion of naked poses) were not produced. For many years the problem was linked to social taboos surrounding the genre and the prevailing moralism of the 19th century: these are quite plausible explanations for the evanescence of the "noble" photographic tradition of the nude, a practice which for many years was forced to remain totally subordinate to the aesthetic canons prevailing in the world of painting.

Although it was with Muybridge and his studies of movement that photography began to reveal the human body in a context transcending that of its voyeuristic manipulation and aesthetic finalization, it was Edward Weston who founded modern nude photography, with his images of a statuary solemnity, a perfection of detail and formal expression. Weston's nudes are perhaps the first to offer a vision that succeeded in espressing - together with the pliant potency of the human form (which Weston investigated within himself and which since then has been taken as a pretext for every free interpretation of the real) - that sort of interior wealth to be found in all things when examined in depth.

In the meantime, another "school" repeated the statuary plasticity of Weston's nudes, at least as concerns the assonance of results, but without approaching his interior force: what in Italy first, with Fascist art, and later in Germany with the art of the Third Reich, proposed as the mythical nude of the great hero, the expression of racial purity, whether Roman or Aryan, connected with the conception of the nude which, from Ancient Greece through Rome and the Renaissance, had come down to the mythicised photographic iconography of Baron Von Gloeden and so many other "aesthetes" enamoured of the solar spontaneity of the Mediterranean.

The reaction against the Academic in its most outworn form pushed the historical avant-garde towards the use of the human body in absolutely disenchanted, and sometimes provocatory, terms. From the Dada of Man Ray to the form-structure of Moholy-Nagy, from the assembly of John Heartfield to the mirrors of Florencie Henri, from the revisited expressionism of Otto Umbher to the first surrealistic images of Bill Brandt, the blossoming of nude images bore witness to the overcoming of 19th-century moralistic taboos and to the assumption of the photographic procedure as a full-fledged instrument in artistic research. In such a way, the contribution of the historic avant-garde to the development of photography, and that of the nude in particular, went hand in hand with the "purist" line.

From the first to the fourth decades of the 20th century, photography of the nude made a decisive step forward: the human figure became one of the favourite subjects of the camera (perhaps psychoanalysis, which had taken just as decisive a step forward, was not foreign to this).

And approaches to the genre began to diverge: Brassai's reportages of a sociological nature, with his photos of Paris nights focusing attention on a reporter's-eye view of the bodies of the "filles de joie" on sale, the female nudes made unreal by a dreamlike soft focus and by the mythological setting in the stylistic features of the great fashion photographers Cecil Beaton and Hoyningen-Huene, Martin Munkacsi or Georges Platt Lynes; the exasperated optical "play" on and deformation of the female figure, somewhere between Dadaism and Surrealism, of Andre' Kertesz, the broadening of vision offered by Bill Brandt's wide-angle lens; the technical and compositional research of Sam Haskins to the triumph of the pin-up girls in the tradition of the large calendar; the function of "creative engineering" offered by the female body in the structuralist and constructivist research of Lazlò Moholy-Nagy and the great school of "pure photography" (in a vision of such rarified tones as to approach mysticism) of Paul Strand, Alvarez Bravo or Harry Callahan.

If it is true, as actor Spike Milligan maintains, that 1960, the year of the trial and acquittal of "Lady Chatterley's Lover", marked the real death of Queen Victoria, it is just as true that since then nude photography has developed in complete freedom and boldness, as well as in great variety. Today, it is fully accepted as a potential work of art, on the same level as painting and sculpture, although its conventions differ from those of other forms of expression. Even eroticism has become nothing more than an episodic and secondary ingredient and has lost part of its subversive attraction in times when the view of naked human bodies is no longer a rarity.

The body of Woman has thus become - at least in the most attentive forms of photography, where it is considered a privileged subject - one of the most perfect "forms", many-sided, richest in suggestiveness and "qualities" to be explored, revealed, exalted.

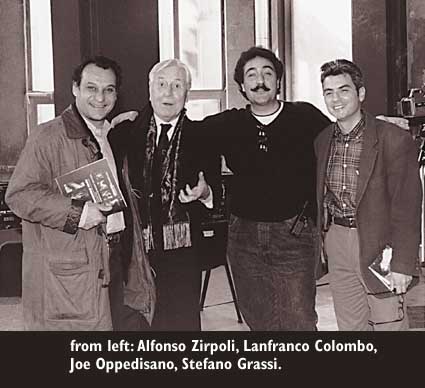

This extended re-view of the paths followed by the nude in photography ex-plains the different clefs in which Stefano Grassi, Joe Oppedisano and Alfonso Zirpoli modulate their research, each in his own way, on the nude.

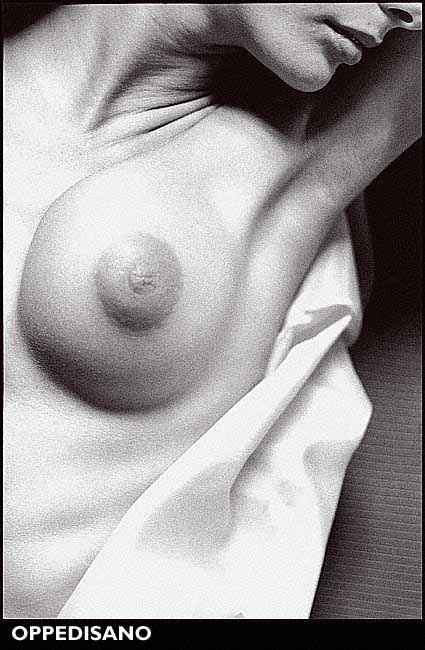

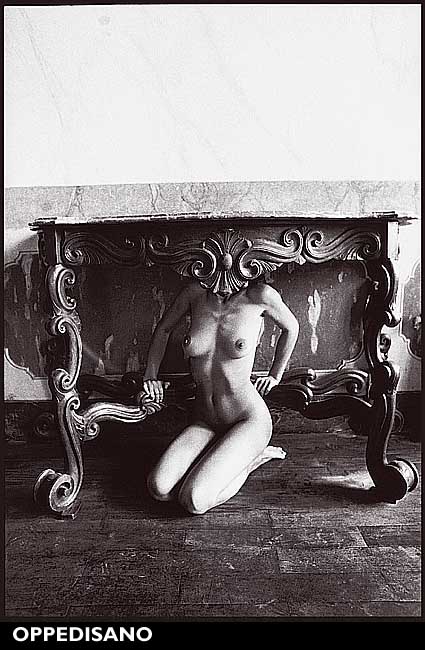

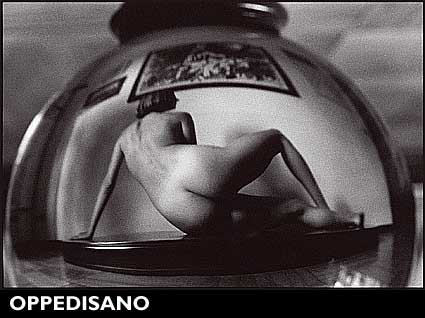

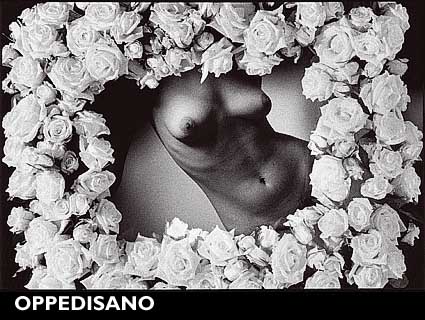

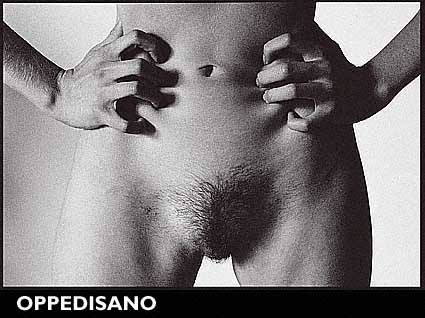

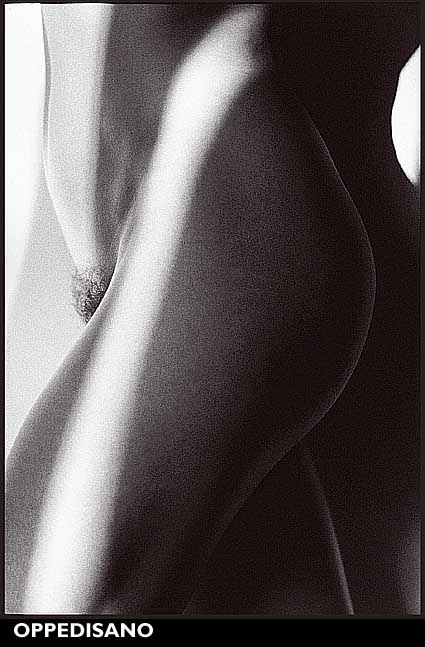

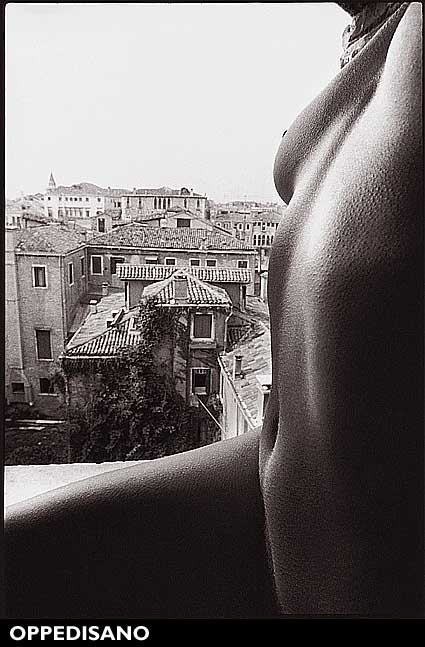

Eclecticism appears to me to be Oppedisano's dominant theme; through a series of "tributes", he retraces the route of the "genre" through the most recent seasons, stopping here and there to repeat certain visionary scenes of Surrealism, to recreate Newton-like atmospheres pregnant with a luxurious calm and voluptuousness, to play at a sort of reportage veined with metaphysical sociology, to evoke phantasmic presences of a conceptual nature, to caress with light and velvety shadow a body in the style of Sieff, to make monumental fragments of a nude as we find in Brandt, to "reveal" - in the series I enjoyed the most - the softness of a perfect form with delicate brush strokes of light delineating a plastic sensuality.

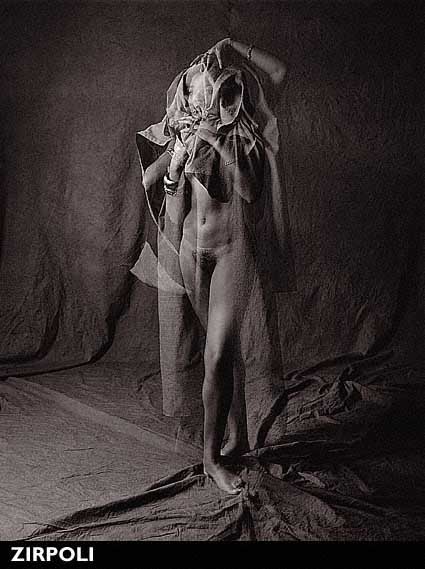

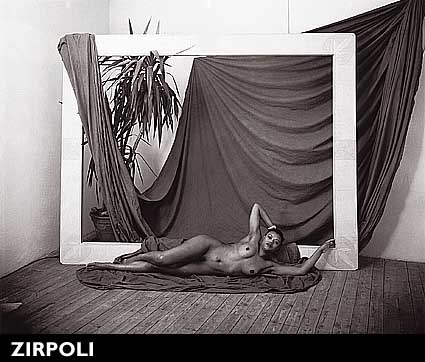

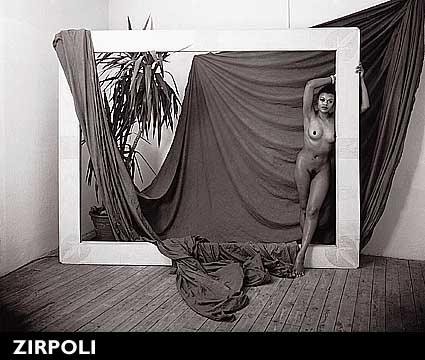

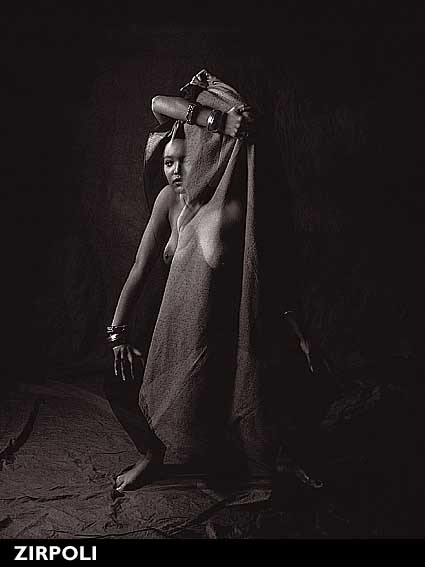

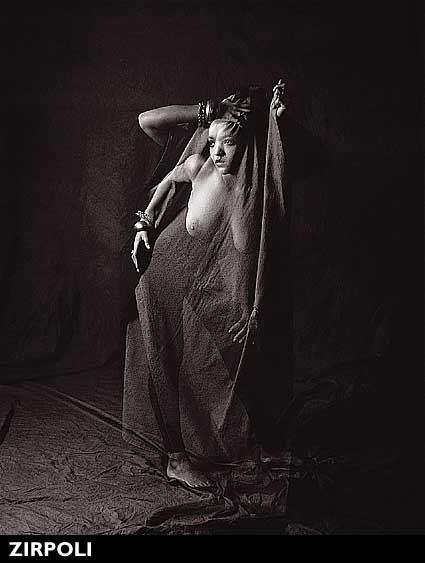

As I see it, a similar eclecticism, although manifested in quite a different way, appears in the work of Zirpoli, who on the one hand - and this is my personal preference - shows much attention to the scenic construction of a reciting imagination and, on the other hand, a commitment to a work of deconstruction into fragments of the elements making up the female body. The extremely artificial geometries against which his models recite their play on the dressed/undressed body - changing from witches, to urchins, to Cassandras and to Penelopes - appropriate modules inferred from Surrealism and place them in rarefied metaphysical atmospheres that attenuate individual characterisation and encase it within phantasms. From this arise "stage characters" who, even when they seem to allude to reminiscences of Francis Bacon (especially in the negation of the faces, which also subtends the lesson of Christian Vogt), are quite familiar to our imaginations and thus appear far more soothing.

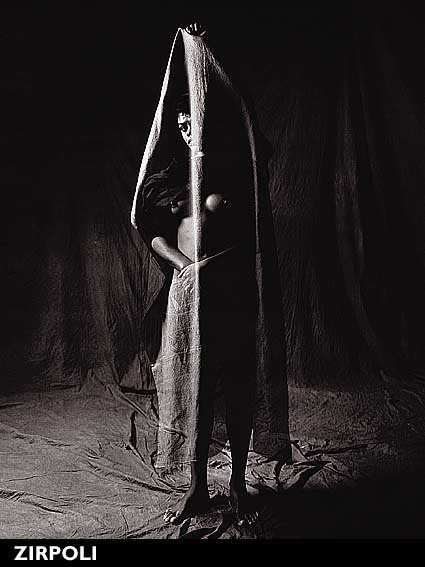

In another investigation, Zirpoli applies exasperated modules of an exclusively photographic nature, in an almost anatomical exploration of the female nude, lingering on it with a bold, aggressively sensual, extremely virile gaze. A shearing illumination exasperates the low tones and places a note of gloom in the atmosphere of this insistent search for plasticity and disclosure.

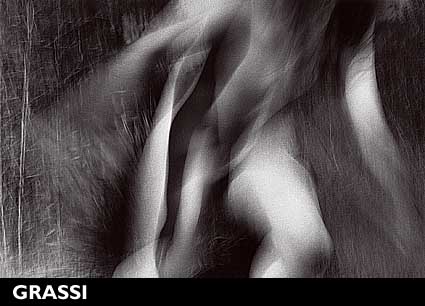

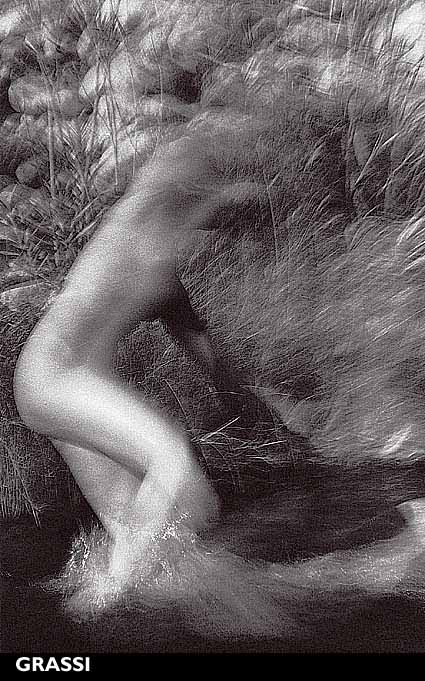

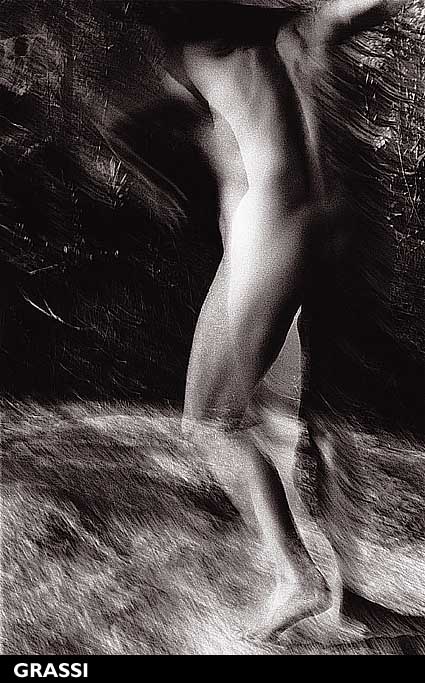

Turning to Grassi's coherent and rigorous

work, the subject of which appears to me far more a concept of physicalness

and dynamism rather than one of the supple beauty or erotic fascination

of the naked body, I see that in these photographs the female nude, at other

times assumed as the "measure" and "interpretation"

of the nature surrounding it (and thus of the world), has become progressively

drained, to the point where it has totally lost the connotations of photographic

realism. By means of blurring (a photographic "effect" that exploits

the constituent elements of the procedure, thus disrupting its historical

function), Grassi takes possession of space and time, as well as their mutations,

and transfers them to another universe, one that approaches the transcendental.

One in which the female body, little more than traced and as if it were

outcropping from intermittent signals of memory, becomes a dynamic ideogram,

melting into the world, evoking and interpreting phantasms, dreams and desires.

Lanfranco Colombo

(translation by David Nilson)