italiano - inglese - back - home

On the borders of purple

If one wished to find the theme that for the past few decades has bound together the work of Wanda Nazzari, which is characterized by a continuity dictated by the rigour of coherence, it could be identified as the fusion of two creative moments: the initial one, marked by the digging into material, and the second one, in which a composition breaks out from the wound thus made, a composition rendered tactile by colour, which also reveals light and shadow. A constant: the colour purple. Research into symbols has demonstrated the value of the chromatic aspect; purple is obtained by mixing two colours, red and blue: the first symbolizes the natural and subterranean forces of land, the second the celestial, spiritual forces. The result is that of complementarity, or rather a synthesis of opposing forces producing a rationality that is not cold, but tempered by the fruits of sentiment: purple is in fact the colour of Temperance. On the tarot card representing it there is an angel with two vases in hand, one blue and the other red; between the two flows a colourless fluid, the water of life. The purple, invisible in this representation, is the result of the perpetual alternating between the red of the force of impulse and the blue of the immateriality of dreams.

The chromatic aspect is

always present in Nazzari's works, starting from her very first experiments,

in which white acquires an absolute value. It is this symbolic meaning of

the colour, which she has assimilated and experienced in the course of her

activities, that over the centuries has drawn the attention of artists and

persons of letters. Leonardo assigned to purple the meaning of universal

harmony, the apparent reconciliation of opposing forces. In our times, suffice

it to mention Steven Spielberg's film The Color Purple taken from the novel

of the same name by Alice Walker, where the expression, attributed to one

of the characters: "I think God gets mad if you pass by something purple

in a field without noticing it", becomes the keynote of the book, through

the pages of which runs a shudder of desperation, which closes with a smile

of hope for a better life: life, for the heroine, will change colours.

The chromatic aspect is

always present in Nazzari's works, starting from her very first experiments,

in which white acquires an absolute value. It is this symbolic meaning of

the colour, which she has assimilated and experienced in the course of her

activities, that over the centuries has drawn the attention of artists and

persons of letters. Leonardo assigned to purple the meaning of universal

harmony, the apparent reconciliation of opposing forces. In our times, suffice

it to mention Steven Spielberg's film The Color Purple taken from the novel

of the same name by Alice Walker, where the expression, attributed to one

of the characters: "I think God gets mad if you pass by something purple

in a field without noticing it", becomes the keynote of the book, through

the pages of which runs a shudder of desperation, which closes with a smile

of hope for a better life: life, for the heroine, will change colours.

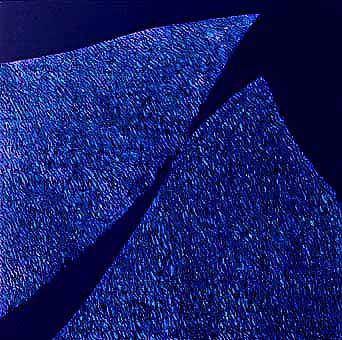

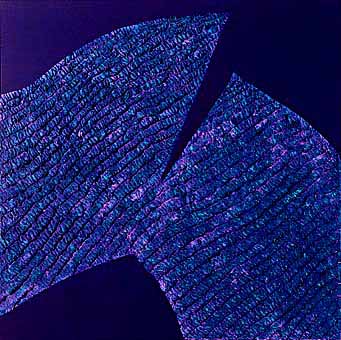

Wanda Nazzari looks prevalently inwards, and in this interior search, a sort of journey through the soul, she attempts to respond to our many questions about life, she strives to penetrate to the core of experience, even the most painful, and to take from these depths the strength to exist, which she also transmits to those who observe her works, which represent a solitary, difficult journey, but one that leads us toward a goal illuminated by the light of hope. All this lies at the roots of her research: the artist, starting from experiences close to graphic techniques, has refined her skills through the masterly use of materials which, even when paper, reveal a rational and logical application producing optical effects responding to a three-dimensional conception which, even in her first period, led her in the direction of sculpture. In fact, thinking of Wanda Nazzari, one wonders if perhaps the most appropriate term that now describes her artistic work might not be sculpture, even though for her, one who is constantly experimenting with the new, endowed with noteworthy and many-faceted skills, there is the risk of the definition taking on a generic and conventional meaning, useful only in describing the artist who works in three dimensions. Her raw material is not bronze or marble, but the space within which she forges her creations: a space transformed into imagination that embraces those who penetrate into it and precipitates them into a non-place where the mind loses the familiar and tranquillizing reference points of traditional three-dimensional sculpture.

The materials used are the simplest and most elementary: but in appearance only, because the way in which they (mostly wood) are employed imparts to them an almost paradigmatic value and produces a complex perceptive image. The hands of the artist dig into the wood against the grain with the small utensils of the etcher, producing small wounds, wounds that appear to be caused by the slow erosion of weather; when wider and deeper, they appear to be caused by the heat of the fire that has burned the wood but has not destroyed it. The wealth of expressive forms that can be obtained from a raw material like wood was amply shown by an interesting research project conducted in France in 1992 under the title La sculpture sur bois with reference to the works of artists of different nationalities.

The wooden pieces of the Polittici live on, strong and proud of their wounds, like trees that have survived a lightning bolt, finding the strength to go on living in the reserves nature has abundantly provided them with. On approaching the "canvases", constructed and assembled with great participatory and creative intensity, one has the sensation of being attracted by a current that destabilizes our realities and through which one enters a dreamlike universe, full of a sense of the unknown and the infinite. But in this universe one does not perceive the ineluctability of an engulfing and destructive space, but rather the serenity of a comfortable hideaway, a place of recollection, reflection, a corner for meditation and, why not, a place of prayer that each of us could adapt to our single existential realities by rearranging the single pieces. Observing that chip of fiery matter detached from the central nucleus now living its own life on a wall, we have a reassuring impression, like that of a warm and luminous star : our thought goes to the Nidi, a separate page, one that is well delineated in the artist's activity, starting from the early 1990s. With a sensitivity that leads to human participation in individual and cosmic suffering, Nazzari sees in the "nest" a construction a sanctuary where one can shut oneself in, meditate, and then open out once again with a conscious perception of the flow of daily life.

Wings, with their highly charged symbolic meanings, become the indispensable means for moving lightly in the spaces of the spirit: they close against the body when one huddles within one's thoughts, they open to the fullest when one flies high and lightly towards a dimension that transcends the human condition, but recalling their limitedness, as in the tragic myth of Icarus. In Nazzari's wooden panels, which are always characterized by the working in scales, the Frammenti assume the value of polarities attracting one another and touching only at the end, in a space that is interiorized through the colour purple, which evokes a deep and faraway force that assumes bodily form in the coarse and at the same time fine material: coarseness and fineness, when analyzed in depth, also represent apparently contrasting polarities which find, however, the possibility of conjunction in their force of attraction.

It is not easy to make comparisons, to place side by side the works of Nazzari and those of other artists, especially contemporary ones. And comparisons are always questionable and are to be understood within the context of commonly shared experiences that cannot always be documented. But if one name can be mentioned it is that of Emilio Vedova who, starting from the 1960s, with his Plurimi in wood, broke through the hoary space of framed pictures to turn it over around the person immersed in it and, at the same time, coloured his works in wood with a lumpy and profound gloomy black from which emerged white, and sometimes red lacerations denoting the artist's rage against capitalistic society. But there is no rage in Nazzari; there is an interior poeticalness, a deeply-felt belief in a better world; thought cannot stop at a comparison: Chi brucia un libro brucia un uomo is one of Vedova's works in iron completed in 1993 for the Library of Sarajevo, full of suffering, but also of hope. The same hope appears in all its promise and luminosity, but still with the charge of suffering that comes with it, in a great installation by Nazzari in the same year, the manger scene A Sarajevo ancora.

WANDA NAZZARI

Cagliari (Italy), 1935

Wanda Nazzari's artistic and cultural formation developed in Cagliari, Italy, the city in which she lives and works. After her first experiences with painting, which go back to the 1950s, the artist remained for a long time far from the art world. It was only in the 1970s that Nazzari went back to painting; at the same time she worked to define and delve more deeply into the terms of her aesthetic investigation. In 1980 she set up her first personal exhibition and began a study of the techniques of traditional and experimental etching and copperplate engraving. From this experience Nazzari arrived at a fortunate intuition and oriented her research in the direction of a more and more decidedly spatial dimension. From canvas to wood, from colour to the concrete texture of a gouged-out sign: this was the outset of an exploration that led to the three-dimensional works of the 1990s the Polyptyches plastic presences that interact with their surroundings and define the work as an object. In her more recent works, represented by large-scale installations, the artist accompanies her investigation of physical space with a profound reflection on the space of the soul. Since 1988 she has worked as a scene designer and artistic consultant in advertising, represented by many publications and video tapes. In 1993 she held a workshop in copperplate technique at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Cagliari together with the Chair of the History of Design, Etching and Graphics. Since 1995 she has been the Art Director of the Man Ray Cultural Centre in Cagliari, a multipurpose space devoted to contemporary research.

![]()

1997 - M.Magnani, Le

frontiere tra incisione e pittura, La Nuova Sardegna.