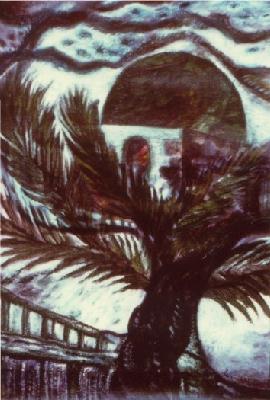

From Tauromachie (Bullfighting) by Rossana Bossaglia (art historian and critic)

(Essay from the volume "Labirinti", 1999)

Cannạ's bull is certainly a victim. Destined to a bloody death, the beast's superb wild head, with its overwhelming vitality, immediately becomes the symbol of a macabre trophy. Cannạ manages, with unique expressiveness, to convey both a sense of vigorous, brutal innocence and that of an instinctive awareness of pain. A hint of supreme melancholy overlies the excitement stamped on his face. This melancholy, however, is not just due to his awareness of being a designated victim, but the fruit of deep existential contemplation. Michele Cannạ, an artist of vigorous style, knows how to endow his characters with energy and authority to an extraordinary degree. This is a gift which owes much to Cannạ the theatre artist and creator of masks, whose work acts not as a simplification but as a sublimation of individual psychologies. Cannạ's painting technique reflects this quality. It is incisive and takes on warm tones when tackling the physical side of his characters, turning them into a direct physical presence. On the other hand, his black and white works, particularly his drawings, tell their stories as if in counterpoint, in the half-dimness of non-colour. The physical power, however, remains, while the subtle, energetic lines of his excellent etchings perfectly convey the bristly luxuriance of the animal's fleece.