|

A.S.S.E.Psi.

web site (History of Psychiatry and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

)

A.S.S.E.Psi.NEWS

(to subscribe our monthly newsletter)

Ce.Psi.Di. (Centro

di Psicoterapia Dinamica "Mauro Mancia")

Maitres

à dispenser (Our reviews about psychoanalytic congresses)

Biblio

Reviews (Recensioni)

Congressi

ECM (in italian)

Events

(our congresses)

Tatiana Rosenthal

and ... other 'psycho-suiciders'

Thalassa.

Portolano of Psychoanalysis

PsychoWitz - Psychoanalysis and Humor (...per ridere un po'!)

Giuseppe Leo's Art

Gallery

Spazio

Rosenthal (femininity and psychoanalysis)

Psicoanalisi

Europea Video

Channel

A.S.S.E.Psi. Video

Channel

Ultima uscita/New issue:

"Psicoanalisi in Terra Santa"

Edited

by/a cura di: Ambra Cusin & Giuseppe Leo

Prefaced by/prefazione

di:

Anna Sabatini Scalmati

Writings by/scritti di:

H. Abramovitch A. Cusin M. Dwairy A. Lotem M.

Mansur M. P. Salatiello Afterword

by/ Postfazione

di:

Ch. U. Schminck-Gustavus

Notes by/ Note di: Nader Akkad

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collection/Collana: Mediterranean

Id-entities

Anno/Year:

2017

Pagine/Pages:

170

ISBN:978-88-97479-12-3

"Essere bambini a Gaza. Il trauma

infinito"

Authored

by/autore: Maria Patrizia Salatiello

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collection/Collana: Mediterranean

Id-entities

Anno/Year:

2016

Pagine/Pages:

242

ISBN:978-88-97479-08-6

Psychoanalysis,

Collective Traumas and Memory Places (English Edition)

Edited

by/a cura di: Giuseppe Leo Prefaced by/prefazione

di:

R.D.Hinshelwood

Writings by/scritti di: J. Altounian

W. Bohleber J. Deutsch

H. Halberstadt-Freud Y. Gampel

N. Janigro R.K. Papadopoulos

M. Ritter S. Varvin H.-J. Wirth

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collection/Collana: Mediterranean

Id-entities

Anno/Year:

2015

Pagine/Pages:

330

ISBN:978-88-97479-09-3

"L'uomo

dietro al lettino" di

Gabriele Cassullo

Prefaced

by/prefazione di: Jeremy

Holmes

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collection/Collana: Biografie

dell'Inconscio

Anno/Year:

2015

Pagine/Pages:

350

ISBN:978-88-97479-07-9

Prezzo/Price:

€ 29,00

Click

here to order the book

(per Edizione

rilegata- Hardcover clicca qui)

"Neuroscience

and Psychoanalysis" (English Edition)

Edited by/a cura di: Giuseppe Leo Prefaced by/prefazione

di: Georg Northoff

Writings by/scritti di: D. Mann

A. N. Schore R. Stickgold

B.A. Van Der Kolk G. Vaslamatzis M.P. Walker

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collection/Collana: Psicoanalisi e neuroscienze

Anno/Year: 2014

Pagine/Pages: 300

ISBN:978-88-97479-06-2

Prezzo/Price: € 49,00

Click

here to order the book

Vera

Schmidt, "Scritti su psicoanalisi infantile ed

educazione"

Edited by/a cura di: Giuseppe Leo Prefaced by/prefazione

di: Alberto Angelini

Introduced by/introduzione di: Vlasta Polojaz

Afterword by/post-fazione di: Rita Corsa

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana: Biografie dell'Inconscio

Anno/Year: 2014

Pagine/Pages: 248

ISBN:978-88-97479-05-5

Prezzo/Price: € 29,00

Click

here to order the book

Resnik,

S. et al. (a cura di Monica Ferri), "L'ascolto dei

sensi e dei luoghi nella relazione terapeutica"

Writings by:A.

Ambrosini, A. Bimbi, M. Ferri, G.

Gabbriellini, A. Luperini, S. Resnik,

S. Rodighiero, R. Tancredi, A. Taquini Resnik,

G. Trippi

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana: Confini della Psicoanalisi

Anno/Year: 2013

Pagine/Pages: 156

ISBN:978-88-97479-04-8

Prezzo/Price: € 37,00

Click

here to order the book

Silvio

G. Cusin, "Sessualità e conoscenza"

A cura di/Edited by: A. Cusin & G. Leo

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana/Collection: Biografie dell'Inconscio

Anno/Year: 2013

Pagine/Pages: 476

ISBN: 978-88-97479-03-1

Prezzo/Price:

€ 39,00

Click

here to order the book

AA.VV.,

"Psicoanalisi e luoghi della riabilitazione", a cura

di G. Leo e G. Riefolo (Editors)

A cura di/Edited by: G. Leo & G. Riefolo

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana/Collection: Id-entità mediterranee

Anno/Year: 2013

Pagine/Pages: 426

ISBN: 978-88-903710-9-7

Prezzo/Price:

€ 39,00

Click

here to order the book

AA.VV.,

"Scrittura e memoria", a cura di R. Bolletti (Editor)

Writings by: J.

Altounian, S. Amati Sas, A. Arslan, R. Bolletti, P. De

Silvestris, M. Morello, A. Sabatini Scalmati.

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana: Cordoglio e pregiudizio

Anno/Year: 2012

Pagine/Pages: 136

ISBN: 978-88-903710-7-3

Prezzo/Price: € 23,00

Click

here to order the book

AA.VV., "Lo

spazio velato. Femminile e discorso

psicoanalitico"

a cura di G. Leo e L. Montani (Editors)

Writings by: A.

Cusin, J. Kristeva, A. Loncan, S. Marino, B.

Massimilla, L. Montani, A. Nunziante Cesaro, S.

Parrello, M. Sommantico, G. Stanziano, L.

Tarantini, A. Zurolo.

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana: Confini della psicoanalisi

Anno/Year: 2012

Pagine/Pages: 382

ISBN: 978-88-903710-6-6

Prezzo/Price: € 39,00

Click

here to order the book

AA.VV., Psychoanalysis

and its Borders, a cura di

G. Leo (Editor)

Writings by: J. Altounian, P.

Fonagy, G.O. Gabbard, J.S. Grotstein, R.D. Hinshelwood, J.P.

Jimenez, O.F. Kernberg, S. Resnik.

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana/Collection: Borders of Psychoanalysis

Anno/Year: 2012

Pagine/Pages: 348

ISBN: 978-88-974790-2-4

Prezzo/Price: € 19,00

Click

here to order the book

AA.VV.,

"Psicoanalisi e luoghi della negazione", a cura di A.

Cusin e G. Leo

Writings by:J.

Altounian, S. Amati Sas, M. e M. Avakian, W. A.

Cusin, N. Janigro, G. Leo, B. E. Litowitz, S. Resnik, A.

Sabatini Scalmati, G. Schneider, M. Šebek,

F. Sironi, L. Tarantini.

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Collana/Collection: Id-entità mediterranee

Anno/Year: 2011

Pagine/Pages: 400

ISBN: 978-88-903710-4-2

Prezzo/Price: € 38,00

Click

here to order the book

"The Voyage Out" by Virginia

Woolf

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

ISBN: 978-88-97479-01-7

Anno/Year: 2011

Pages: 672

Prezzo/Price: € 25,00

Click

here to order the book

"Psicologia

dell'antisemitismo" di Imre Hermann

Author:Imre Hermann

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

ISBN: 978-88-903710-3-5

Anno/Year: 2011

Pages: 158

Prezzo/Price: € 18,00

Click

here to order the book

"Id-entità mediterranee.

Psicoanalisi e luoghi della memoria" a cura di Giuseppe Leo

(editor)

Writings by: J.

Altounian, S. Amati Sas, M. Avakian, W. Bohleber, M. Breccia, A.

Coen, A. Cusin, G. Dana, J. Deutsch, S. Fizzarotti Selvaggi, Y.

Gampel, H. Halberstadt-Freud, N. Janigro, R. Kaës, G. Leo, M.

Maisetti, F. Mazzei, M. Ritter, C. Trono, S. Varvin e H.-J. Wirth

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

ISBN: 978-88-903710-2-8

Anno/Year: 2010

Pages: 520

Prezzo/Price: € 41,00

Click

here to have a preview

Click

here to order the book

"Vite soffiate. I vinti della

psicoanalisi" di Giuseppe Leo

Editore/Publisher: Edizioni Frenis Zero

Edizione: 2a

ISBN: 978-88-903710-5-9

Anno/Year: 2011

Prezzo/Price: € 34,00

Click

here to order the book

"La Psicoanalisi e i suoi

confini" edited by Giuseppe Leo

Writings by: J.

Altounian, P. Fonagy, G.O. Gabbard, J.S. Grotstein, R.D.

Hinshelwood, J.P. Jiménez, O.F. Kernberg, S. Resnik

Editore/Publisher: Astrolabio Ubaldini

ISBN: 978-88-340155-7-5

Anno/Year: 2009

Pages: 224

Prezzo/Price: € 20,00

"La Psicoanalisi. Intrecci Paesaggi

Confini"

Edited by S. Fizzarotti Selvaggi, G.Leo.

Writings by: Salomon Resnik, Mauro Mancia, Andreas Giannakoulas,

Mario Rossi Monti, Santa Fizzarotti Selvaggi, Giuseppe Leo.

Publisher: Schena Editore

ISBN 88-8229-567-2

Price: € 15,00

Click here to order the

book |

Introduction

This paper explores the inspiration of psychoanalysis and critical

theory in the generation and interpretation of auto/biographical

narratives with particular reference to fundamentalism. The latter can

be seen to represent, in its closure to others and otherness, the

antithesis of some of the ideals of adult popular education. This

essay draws on recent research into the rise of racism and

fundamentalism, as well as the historical and contemporary role of

adult education, in what is now a post-industrial city in England

(West, 2016a&b). Adult education, past and present, can generate

‘resources of hope’, in Raymond Williams’ compelling phrase, for

democratic experiment (Williams, 1989). In the spirit of Kirsten

Weber, the paper’s theoretical sweep encompasses the dynamic

interplay of culture and psyche. It specifically draws on the work of

Donald Winnicott and Axel Honneth to consider processes of

self-recognition in human flourishing. Honneth draws in fact on John

Dewey to consider the prerequisites for a radical, far-reaching

understanding of ‘a cooperative contribution to social

reproduction’, and of what inhibits this. He argues that the mature

Dewey provides ‘an alternative in the end of work society’ where

we can ‘no longer assume the form of a normatively inspired

restructuring of the capitalist labour market’ (Honneth, 2007: 236).

Nevertheless, any impetus towards cooperation has to be set against

the dynamics of disrespect and how these can infuse racist or

fundamentalist groups, driving people towards alienation from one

another.

I want to suggest that our intimate vulnerabilities and need to be

loved are played out in the wider society, which explains the

attractions of the racist gang or Islamist group. We can feel

recognised there by significant others and in turn feel that we belong,

providing a basis for self-respect. But we may also be seduced by

totalising narratives that close us down to others and otherness in

the name of truth. Processes of psychological spitting take over in

what become paranoid/schizoid modes of functioning. Paranoia is

generated by fear of the other, rooted in anxieties about inadequacy,

while splitting involves projecting negative parts of our selves and

culture on the other; these are parts, or ‘objects’ that we may

most dislike in ourselves and people like us. Our own culture is then

idealised.

The best of adult education, on the other hand, is grounded in an

ideal of equality, respect, trust, dialogue as well as diversity and

openness to the other. It has generated processes of self-recognition,

including of bigotry within, as well as recognition of the other and

awareness of the complexities of knowledge and sensitivity towards

different ways of knowing. (Although there are fundamentalist

tendencies in all groups, including workers’ education. Some of the

autodidacts in the history of British popular education could be rigid

and uncompromising in their views, fuelled by dissenting

‘religious’ beliefs. Their adoption of particular versions of

Marxism could drive them towards an intolerant defensiveness (West,

2016a)). My other paper at this Conference focuses on the best of

adult education, then and now, in the city, and its centrality in

cultivating democratic sensibilities (West, 2016b). The present paper

focuses on disrespect and psychosocial dynamics in specific Islamist

groups.

Distress

in the city

In

2008, I was greatly troubled by the rise of racism and fundamentalism

in the ‘postindustrial’ city of my birth, Stoke-on-Trent, in the

English Midlands. In 2008/9 the racist British National Party (BNP)

was strengthening its presence in parts of the city and a mosque was

pipe-bombed. It seemed that racists would form the majority on the

Municipal Council by 2010 (West, 2016a). There were incidents of

racial violence and outbursts of Islamophobia. The economic base of

the city had long since unravelled and its politics were in chronic

crisis, with low levels of engagement in voting. The traditional

employment base of the city – coal mining, iron and steel production

and pottery - had disappeared altogether or drastically declined.

Longterm structural unemployment was endemic (West, 2016a). The

financial crisis, from 2008 onwards, and consequent austerity,

including cuts in local government funding, added to the distress. And

adult education, once so important in the city, had been marginalised,

although it continued to do important work.

Historical geographer Matthew Rice (2010) has written that ‘maybe

Stoke-on-Trent’, England’s twelfth biggest city, ‘is just one

industrial city too many’ (p. 17). Yet this city was once home to

vibrant pottery, mining, and iron and steel industries. Hundreds of

thousands of plates, cups and saucers, all packed safely with straw in

barrels or wooden baskets, were sent to food markets in India, Ceylon

(now Sri Lanka), Canada, Australia, New Zealand and America. In 1925,

100,000 workers were employed in the pottery industry. By 2009 the

figure was about 9000. Rice notes that wages were never high in Stoke,

and cheap labour came to the area from places like Kashmir and the

Punjab in Southern Asia in the 1960s. Low wages in Stoke equated

however to relatively high sources of income for migrant families. But

when outsourcing gathered pace, many of the descendants of those whose

grandparents had migrated were left in a jobless limbo. Having a job

matters for cultural as well as economic reasons, particularly for

young Asian men: to be the head of the family and support its members

is a strong cultural as well as economic imperative.

Auto/biographical

narrative interviewing in a clinical style

I

will explain the use of the auto/biographical narrative methodology,

in a clinical style, informed by psychoanalysis. The stories people

tell are always a reconstruction of events, afterthoughts, rather than

the events themselves, while the powerful discourses of a culture and

unconscious processes of wanting to please or appease circulate in

stories. They can be seen as of little relevance to any bigger picture

of, for instance, democracy in crisis or the rise of fundamentalism

– ‘fine meaningless detail’, as one historian graphically framed

it (Fieldhouse, 1996). Yet we can so much better understand the

nuances of why particular people are attracted to the BNP, or

radicalized, through the lifelong and life-wide lens of auto/biography.

This is its especial power.

For one thing, the general – or bigger – picture is always there

in the particular, not least in the narrative resources people draw on

to tell their stories. We are storied as well as storytellers. Stories

may constrain as well as liberate, as a bigger picture – of

neo-liberal assumptions, say, or of the actions of the Western world

– grip particular accounts. And people can internalize the

negativities about ‘people like us’, whether emanating from the

mouths and projections of politicians, policymakers or the mass media.

Those targeted may be struggling on benefits or single parents, as

chronicled in my earlier work in other marginalized locations (Merrill

and West, 2009). People can feel themselves to be the racist objects

of society’s disdain, caught in the gaze of the judgemental other

and constantly needing to justify themselves. Those on the margins

easily internalize negative projections, or feel inadequate (West,

2007; 2009). Those on the edge have had to learn to deal with many and

varied authority figures day by day: the social worker, the job centre

assessor, the head teacher, the health visitor, researchers, and for

present purposes, racists. They can have wellrehearsed tales to tell

(West, 2009).

But people, it is suggested, are not simply aggregates of certain

sociological or cultural variables. We are living beings with stories

to tell of what it feels like to exist in particular conditions, or to

experience disrespect on the street. Our aspirations and narratives

have validity in their own terms, however difficult and distasteful

these might be. Understanding lives from the inside requires time and

the cooperation of those involved, and an appreciation of research as

a legitimate process for them, an opportunity to tell and think about

their stories. Interpretation also requires what I term a psychosocial,

historical and educational imagination, one that reminds us that

people are psychosocial agents rather than marionettes on a

predetermined sociological stage. People make, as well as are made by,

history.

The study sought to illuminate some of the seductions and insecurities

fuelling racism and fundamentalism on a white working class estate and

in areas of the city where Muslim people lives. The 50 or so

participants in the study were in the main ‘ordinary’ people. The

sample was opportunistic – I asked officers of the City Council for

names of people that might be helpful to my work and they in turn

helped me make contact with others. As the research developed, the

sampling became more purposive or theoretical, as I sought to

interview individuals who were attracted, say, to Islamism.

Winnicott, Honneth and Dewey helped me make sense of many stories.

Axel Honneth (2009) refers to Winnicott to emphasise the fundamental

importance of love, in processes of self-recognition, of feeling

understood and legitimate in the world, in our most intimate of

interactions. However, he also interrogates the role of groups in

generating a second category of recognition, which he calls

self-respect. This is when people feel accepted and that they belong,

with rights and responsibilities. Self-esteem provides Honneth’s

third category of recognition. This happens when individuals feel

recognized because they are seen to contribute to a group’s wider

well-being and development (Honneth, 2007; 2009). But then processes

of recognition can be aborted, as the other is experienced,

consciously and unconsciously, as the problem needing to be expunged

in processes of splitting and idealisation.

Islamic

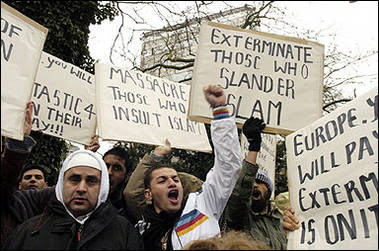

fundamentalism in the city

People

of South Asian origin settled in Stoke came from places like Kashmir,

Pakistan and Bangladesh. They make up about 50 per cent of the city’s

ethnic minority population and in 2011 numbered just over 9000 (Burnett,

2011). Some of these people talked about constant experiences of

disrespect and everyday experiences of Islamophobia: among taxi

drivers, for instance, told frequently to ‘fuck off home’ by white

clients. The sense of everyday disrespect was amplified by stories of

actual physical violence: an Asian man was killed and others injured

as well as mosques damaged. Such experiences of disrespect evoke

insecurity, vulnerability and defensiveness – paranoia even – and

may reinforce the tendency for people to congregate in particular

areas, among their own. Disrespect also ignites the feeling that other

people’s behaviour is wrong, grounded in some normative ideal of

justice.

Islamic fundamentalism has attracted young people in specific mosques.

Small numbers, but they exist. The groups offer the three types of

self-recognition, as described above, of self-confidence, respect and

esteem, but this is then followed by scapegoating narratives and the

stereotyping of difference. The perception of others becomes a

self-motivated distortion accompanied by an idealization of self and

one’s own culture. The pursuit of material wealth or pleasure, for

instance, or the sexualisation of women and a capacity for violence

are projected onto the other of, say, the white working class

estate.

Culturally, it was also clear that relationships between the

generations have suffered, as male initiation rituals between fathers

and sons, in the workplace, are lost. Narratives of the

‘Christian’ neglect of white Muslims in the Bosnian conflict, in

contrast to the ‘Christian’ (that is Russian Orthodox) support for

the ‘Christian’ Serbs, also filled some of this economic and

intergenerational vacuum. In the 1990s actions by the West, standing

back as Muslims were slaughtered, as at Srebrenica, were essentially

seen as anti-Islamic rather than racist, given that Muslims there were

white. Certain young people inwardly digested stories of Muslim

humiliation, collective trauma and ‘Christian’ hostility, and the

need to fight back in ways that previous generations had failed to do.

The political became deeply personal, fuelled by the toxicity of

Islamophobia.

A community leader, who I call Aasif, (the names used are pseudonyms)

talked about these issues:

…

you had groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir taking advantage of the situation

in Bosnia … with what’s happening with the Muslims ... arms not

being allowed to get to the Muslims to defend themselves where Russia

is providing the Christian Serbs; it was a them-against-us kind of

debate with groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir … talking about the male

Muslim section of Muslim community at that time; the youth, low

education achievement, low aspiration … no job opportunity…

perfect audience… you can recruit easy ... It’s nothing to do with

the colour of your skin; this is not racism; this is a target on the

Muslim community because these Muslims are white … I can remember

some of these Hizb ut-Tahrir members who in the early ’90s, pulling

the youth away from the parents as well.

From

this perspective, Bosnia was a trauma, in which scales fell from

collective eyes: it led to increased politicization and provided a

mythic rationale for fundamentalism (Varvin, 2012). Groups like Hizb

ut-Tahrir (or Liberation Party) – حزب

التحرير ,in the Arabic –

exploited such feelings. Hizb ut-Tahrir is an international panIslamic

political organization commonly associated with the goal of all Muslim

countries unifying into one Islamic caliphate, ruled by sharia law.

Hizb ut-Tahrir was founded in 1952 as part of a movement to create a

new elite among Muslim youth. The writings of the group’s founder,

Shaikh Taqi al-Dine al-Nabahani, lay down detailed descriptions for a

restored caliphate (Ruthven, 2012).

There was a further dimension to intergenerational dynamics. Some

young people had little respect for particular imams who had come to

Stoke from their parents of grandparents’ villages in Pakistan,

Bangladesh or Kashmir. Older generations had wanted an emotional link

with home. But the imams had only limited education and poor English.

A young person like Raafe, for example, schooled in England, ridiculed

some of the established authorities in the Mosques.

Raafe

A

community leader, Aatif, told me about the weaknesses of mosque

management and of imams and how Raafe and others exploited this. Raafe,

I was told, was an individual ‘who had a very troubled upbringing’

and had been sent to prison:

…

Raafe didn’t have a very good relationship with his father ended up

in crime … was sent down to prison … Came out of prison and he was

within a few weeks, he was, he had transformed into somebody who was a

practising Muslim now to hear him … later on when we realized he was

part of Hizb ut- Tahrir, but at that point to see somebody change so

dramatically was wow, he made a real positive change ... you couldn’t

explain to your parents why you wanted to … your parents who came in

the early ’60s … came when they were young … so very little …

religious… education … so they didn’t have…opportunity to

question the imams and learn something; so they couldn’t pass that

religious knowledge on to the youth, to their children; so the parents

relied upon the mosques to offer that … so that’s where the

communication barrier helped groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir. We can offer

you Islamic information in your language, that’s what attracted a

lot of people in Stoke-on-Trent on topical issues …

Radicalization

transformed the lives of some individuals, providing meaning, purpose

and self-recognition. Raafe’s transformation almost certainly

depended on feeling understood, listened to and respected by radical

groups in prison. They could well have built up self-confidence and

eventually a radical purpose. Raafe, I was told by various people, was

already an active member of a radical group when he left prison. He

then ran youth discussion groups in particular mosques.

Self-recognition works at an imaginal and narrative as well as

interpersonal level; by association with heroes and causes from the

past, that speak to present needs, however perversely.

The pedagogy of radicalization exploits the vacuums and

meaninglessness in particular lives, giving people a potential place

in history. It involves stories and appeals to action, rather than

textual hermeneutics. Narratives of twelfth- century victories

supported a call for jihad now, one requiring toughness and heroism.

Jihad, or struggle, becomes constructed as a heavy responsibility that

requires brutality to demoralise a more powerful opponent. The victory

of the Muslim armies, led by the King of Jerusalem, Guy of Lusignan,

against the Crusaders in the twelfth century’s Battle of Hattin, is

interpreted as the outcome of a long process of small-scale, hard

hitting attacks in various locations. Past struggles are reinterpreted

in the light of the present in the struggle against the new crusaders

of the West and its client states. Heroism and martyrdom are called

for in what is a very different pedagogical process from rational,

textual analysis of the Qur’an. Muslim clerics may speak in the

language of theory, the jihadi groups act through stories and doing (Hassan

and Weiss, 2015).

Thus Islamophobia and everyday disrespect, when mixed with national

politics, foreign policy adventures and intergenerational fractures

within Muslim communities, draws individuals towards Islamism.

Powerful forms of recognition are provided, which operate at a

primitive emotional, as well as group and narrative level. Individuals

feel understood and find purpose, meaning and legitimacy in the world.

Recognition gives meaning to fractured lives and even ‘divine’

purpose. But in the closed fundamentalist group, the process is

impregnated with misrecognition of the other, and with dialogical and

narrative closure. There is alienation, ironically, from self as well

as otherness in the process. The capacity to engage openly and

reflexivity with experience, in all its messiness, closes down; debate,

dialogue, enquiry and self/other recognition, on which social

solidarities and cooperation ultimately depend, are stifled.

Conclusion:

recognition, fundamentalism and the psychosocial

The

research into radicalisation processes enables us to refine the

concept of recognition. It encompasses, as Honneth suggests,

self-recognition at an intimate emotional, relational, group but also

a narrative level. Moreover, such processes are often largely

unconscious, in that recognition takes us beyond words or discursive

understanding of intimate relations or group formation. Primitive,

emotional forms of communication can make people feel that they are

understood, cared for, loved even; such experience ‘speaks’, at

times, louder than words. Raafe felt cared for in prison, his

struggles and troubles were understood and new narrative resources

were then made available. This enabled him to work with other

alienated young Muslims, to care for them in a way that he was cared

for himself. The other young people no doubt felt recognised by

someone they admired, because he spoke to their concerns (and with an

authority grounded in visits to the Middle East). Raafe also built

narrative connections over time, between their anxieties and those of

Muslims, in the past. Such narratives explained suffering in terms of

attacks on Islam and the need for heroic struggle against crusaders,

then and now. These dynamics, however perverted, provide existential

meaning and the promise, for some, of entry into Paradise. But finally

it is important to emphasise that fundamentalism is no ‘other’,

but rather a dynamic that exists within us all. It has to do with

feeling out of our depth and grabbing at ideas that appear to offer

total solutions, an answer to everything, including our anxiety. We

can all find living in uncertainty difficult, but of course, not

everyone reaches for a Kalashnikov. This is where a subtler

understanding of individual biographies is required, like Raafe’s,

to appreciate the allure of violence in specific lives.

The ‘psychosocial’ theory of recognition developed in the study

encompasses appreciation of shared vulnerability and a common need for

love, affirmation, respect, esteem, dialogue and narrative

meaningfulness. Dependency is hardwired into us in what psychoanalysis

terms ‘memory in feeling’. Our efforts to manage separation and

individuation processes can evoke great anxiety. We need good enough

loving but challenging relationships to do this (Winnicott, 1971).

These primitive dimensions of recognition can play out later in

struggles to be accepted in, and important to, an Islamist group. It

is not so much about having a good opinion of ourselves but the

feeling of a shared dignity of persons who can be morally responsible

agents, capable of purposive action in the world. However, Dewey

(1969) enables us to differentiate between the narrative closure of

the Islamist group and perverted forms of action, and the relative

openness of democratic adult education.

Dewey observed that the good citizen requires democratic association

to realize what she might be: she finds herself by participating in

family life, the economy and various artistic, cultural and political

activities, in which there is free give and take with diverse others.

This fosters feelings of being understood and creates meaning and

purpose in the company of others. Dewey suggests that good and

intelligent solutions for society as a whole stem from relatively

open, inclusive and democratic types of association. In scientific

research, for instance, the more scientists freely introduce their own

hypotheses, beliefs and intuitions, the better the eventual outcome.

Dewey applied this idea to social learning as a whole: intelligent

solutions are the result of the degree to which all those involved in

groups participate fully without constraint and with equal rights. It

is only when openly publicly debating issues, in inclusive ways, that

societies really thrive (Honneth, 2007: 218–39). Honneth concluded

that Dewey’s normative idea of healthy democracy was grounded in a

social ideal of cooperation, rather than politics per se; in openness

to complex experience which may challenge what we think, feel and do.

In the case of a ‘robber band’, (which is an example Dewey himself

gives) or the racist and fundamentalist group, however, there is

closure to others and ultimately to the search for truth. This is a

defence mechanism, operating at a primitive psychological as well as

group level. For this reason, we can legitimately reframe Dewey’s

social ideal as a psychosocial one. When individuals and groups close

themselves off to the other, it needs to be understood in both

personal and culturally defensive ways. Such a psychosocial,

epistemological perspective takes us right back to the inspiration of

Kirsten Weber’s own work.

|

click here

click here ![]() to

read this article in Italian

to

read this article in Italian